Case Study: Tankard

In the American colonies of the 1700s, pewter tankards were expensive and prestigious vessels. In a society known for its consumption of hard cider, beer, and malt, drinking vessels played an important role. Pewter was valued as a luxury item, and a pewter tankard with a lid established the status of the owner and also protected his beverage from insects.

Tankards were particularly popular in New York State, where this example was made. The simple, flat lid and barrel-shape body was considered to be old-fashioned by the mid 1700s. However, the design remained popular in parts of New York for a long time.

Tankard and marks (underside)

Made by Henry Will

New York State; 1761–93

Pewter

1965.2752 Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

Henry Will, a German-born pewterer, made and marked this tankard, probably during the years he spent in Albany, New York. Will’s mark as well as his initials, HW, and three pseudo hallmarks appear on the bottom of the tankard. Although America has no system of hallmarks, pewterers and silversmiths often used pseudo hallmarks on their goods to imitate British practices.

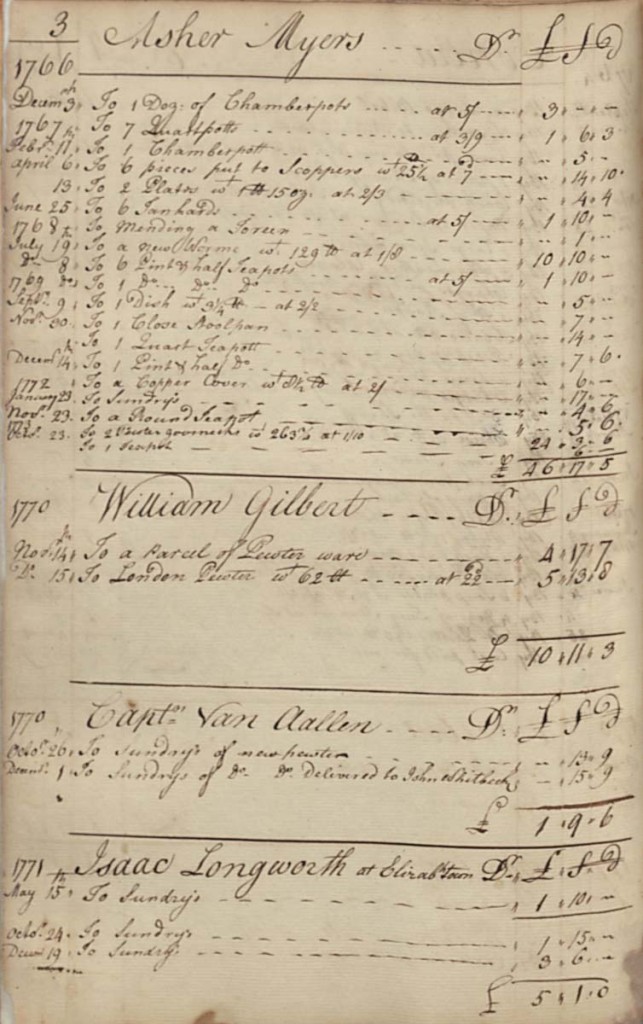

Account book of Henry Will

New York State; 1763–96

Iron gall ink

95×1.1 Downs Collection, gift of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts

Most craftsmen kept account books recording their business transactions. These volumes provide clues about craft and business practices, changing styles, and clientele. Henry Will’s account book reveals that a new pewter tankard cost 5 shillings, one of his most expensive products. Some customers made partial payment to Will in old pewter that he melted to make new vessels. Also, a significant part of Will’s business was repairing old pewter.

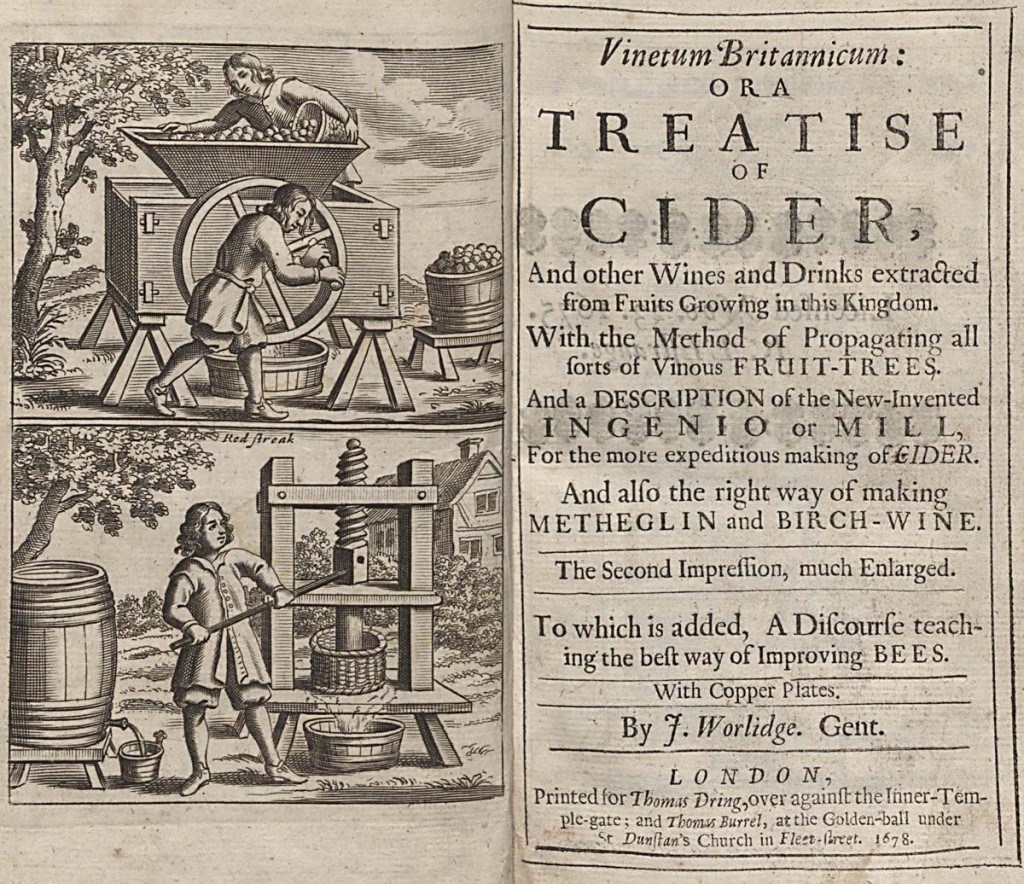

Vinetum Britannicum; or, A Treatise of Cider

By John Worlidge, printed for Thomas Dring

London, England; 1678

Engraving

TP504 W92 Printed Book and Periodical Collection

John Worlidge wrote this treatise to improve the quality and thereby increase the consumption of hard cider, a common beverage in Britain and colonial America. Vessels like the Henry Will tankard were used for beverages like cider.

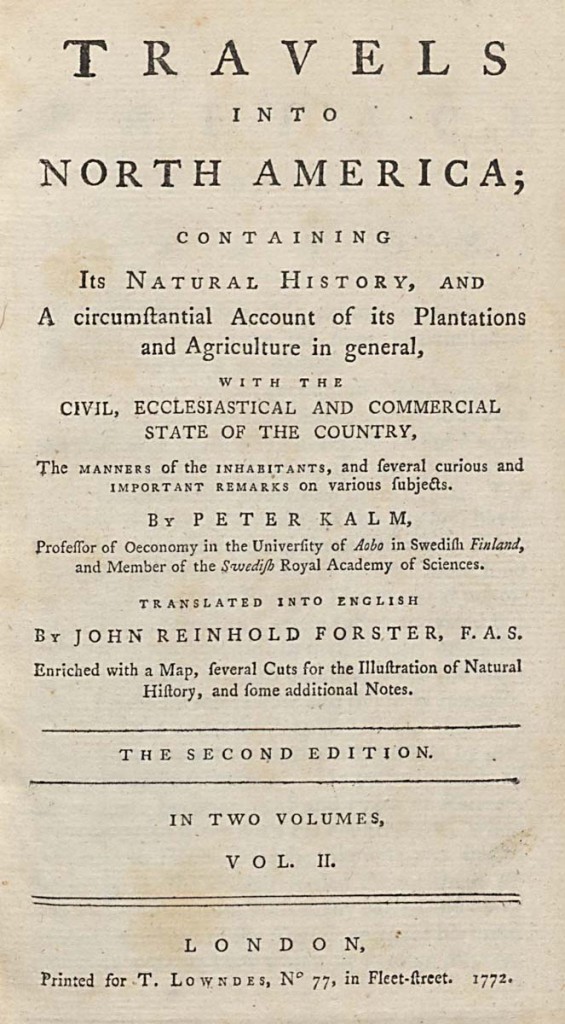

Travels into North America

By Peter Kalm, trans. John Reinhold Foster

Printed by T. Lowndes

London, England; 1772

E162 K14 Printed Book and Periodical Collection

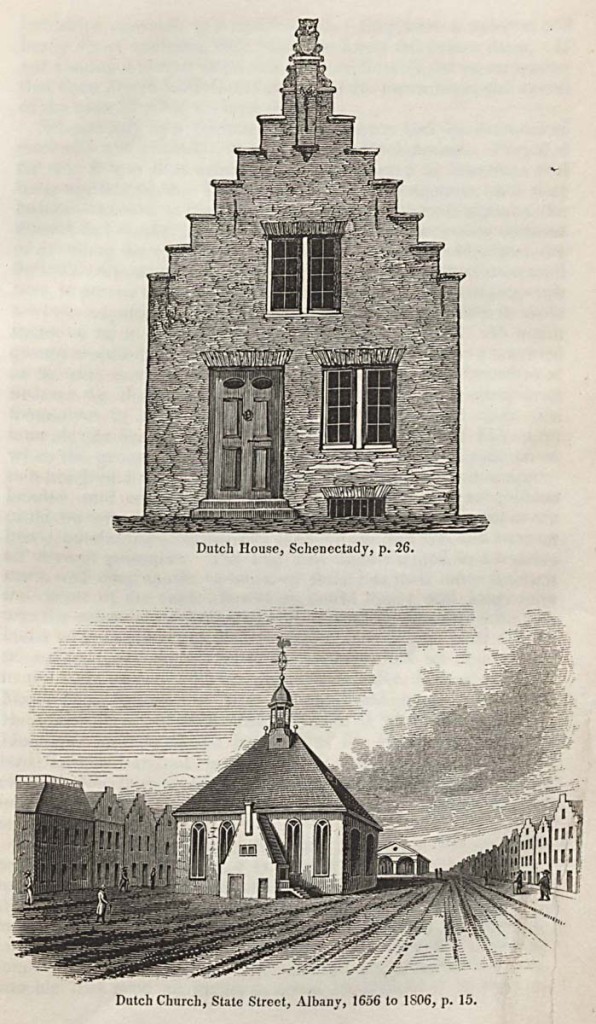

Annals and Occurrences of New York City and State

By John F. Watson, published by Henry F. Anners

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 1846

F119 W33a Printed Book Collection and Periodical Collection

Swedish naturalist Peter Kalm wrote this account of his visit to Albany, New York, in the 1740s. In Albany he found people who still embraced Dutch customs, language, and architecture, as can be seen in the stepped-gable house pictured in the Watson book. This persistence of Dutch culture may explain why Albany residents preferred an old-fashioned tankard style. Kalm also noted a possible reason for the tankard’s popularity: apple orchards were abundant in the area, and they produced excellent hard cider.

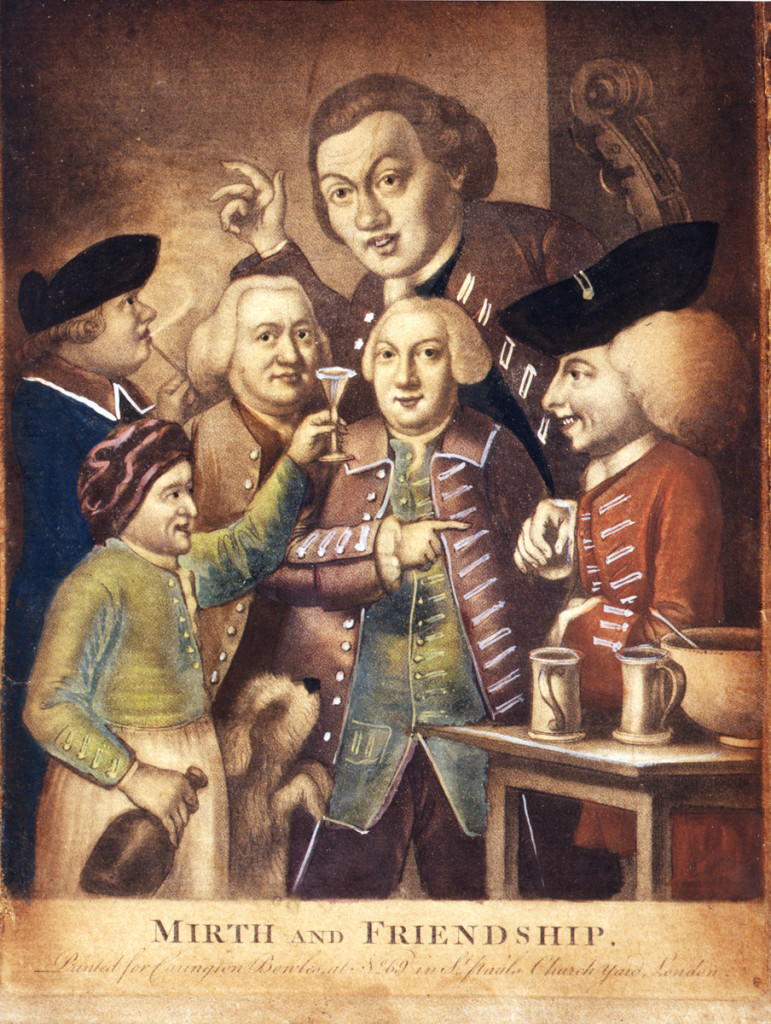

Mirth and Friendship

Mirth and Friendship

Printed for Carington Bowles

London, England; 1775

Hand-colored mezzotint

1987.0042 Gift of George H. Blackshire in memory of his mother, Inez Louise Hamilton Blackshire

Mirth and Friendship illustrates a typical tavern scene featuring a punch bowl and ladle, two lidless tankards, and wineglasses. Lidless tankards, or mugs, were common in taverns. The more expensive lidded tankards, like the Henry Will example, were usually owned by individuals.

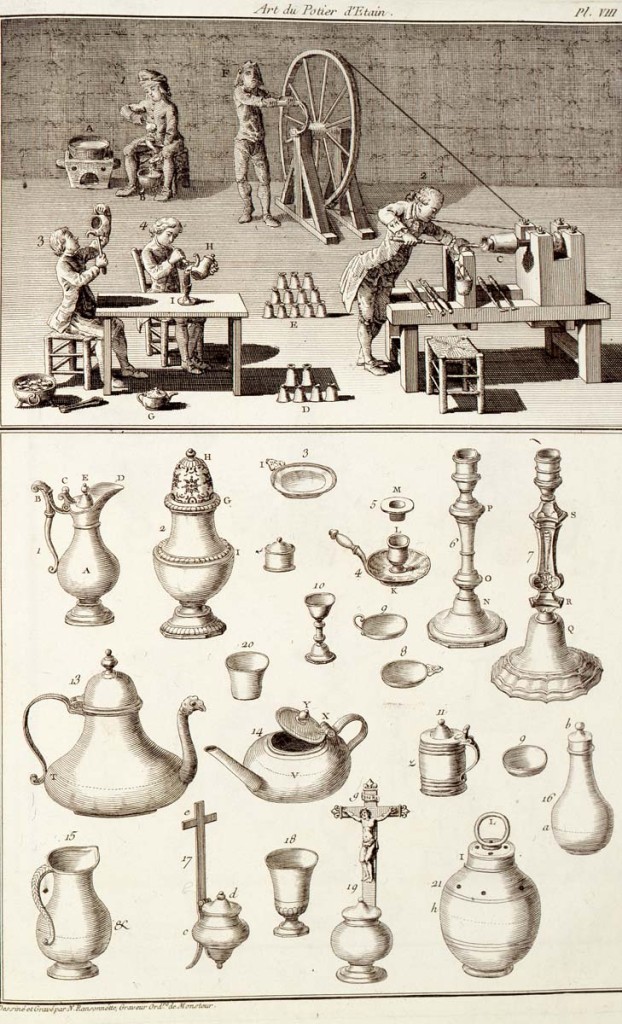

Art du Potier d’Etain

Art du Potier d’Etain

By M.[Pierre-Augustin] Salmon, printed by Moutard

Paris, France; 1788

Engraving

NK8404 S17 F Printed Book and Periodical Collection, gift of the Friends of Winterthur

This volume on pewtermaking is part of the Descriptions des Arts et Métiers, a series of 81 publications issued between 1761 and 1788 that recorded the details of every industrial process in France. The illustrations show each step in making a tankard.

A pewterer melted his ingredients before casting the parts in molds, refining the shapes on a lathe, and then soldering them together. After a final polishing, most pewterers marked their wares to identify the maker and, sometimes, the quality of the metal.

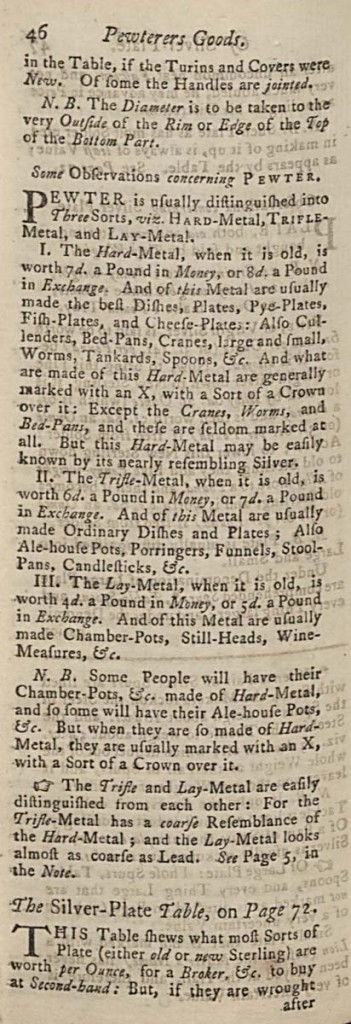

The Compleat Appraiser Consisting of Useful Tables, with Their Explanation for the Valuing of Braziers, Copper-smiths, Plumbers, and Pewterers Goods

The Compleat Appraiser Consisting of Useful Tables, with Their Explanation for the Valuing of Braziers, Copper-smiths, Plumbers, and Pewterers Goods

By an Eminent Broker, lately deceased

London, England; 1783

TP860 P71 Printed Book and Periodical Collection

The Compleat Appraiser provides detailed instructions for identifying and valuing different grades of pewter. Pewter is a mixture of tin, lead, and other metals, but the exact composition varies widely. High-quality pewter is made with a high tin and low lead mixture. Lower-quality pewter contains less tin and more lead.

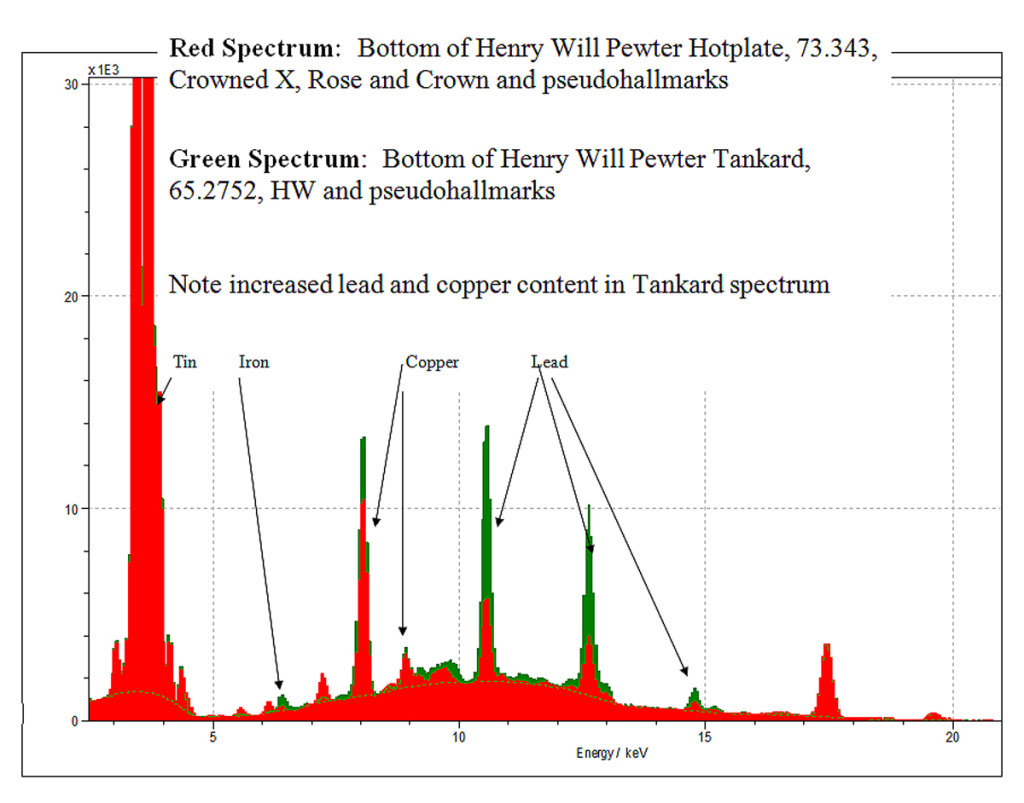

According to The Compleat Appraiser, the highest grade of pewter resembles silver and was commonly marked with a “crowned X.” Lower grades were unmarked and were coarser in appearance. That bit of information, when combined with a scientific analysis of the pewter, has helped museum staff interpret the meaning of the crowned X and quantify the proportions of the metals that are present.

The Henry Will tankard is not marked with a crowned X. It is made of lower-grade pewter than the Henry Will hot-water plate, which is marked with a crowned X. Perhaps Will did not have access to high-quality pewter for the tankard or perhaps his client would not agree to pay for it.

Hot-water plate and crowned X mark (underside)

Hot-water plate and crowned X mark (underside)

Made by Henry Will

New York State; 1761–83

Pewter

1973.0343 Museum purchase

Energy Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) analysis of tankard

Winterthur Scientific Research and Analytical Laboratory

The scientists in Winterthur’s research laboratory determined the chemical composition of Henry Will’s pewter by using energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence testing. This analysis revealed that the marked hot-water plate contains significantly more tin and less lead than the unmarked tankard, confirming that the crowned X mark indicates high-quality pewter.

Related Themes: